What 'Analog Warmth' Actually Is

Everyone talks about analog warmth. Almost nobody can explain what it actually means. Here's my attempt, from someone who's spent way too much time trying to model it in code.

"Analog warmth" might be the most overused term in audio. Everyone wants it. Very few people can explain what it actually is.

Let me take a shot at it, because I've spent a lot of time trying to recreate it in code.

What warmth actually is (technically)

When people say something sounds "warm," they usually mean some combination of these things:

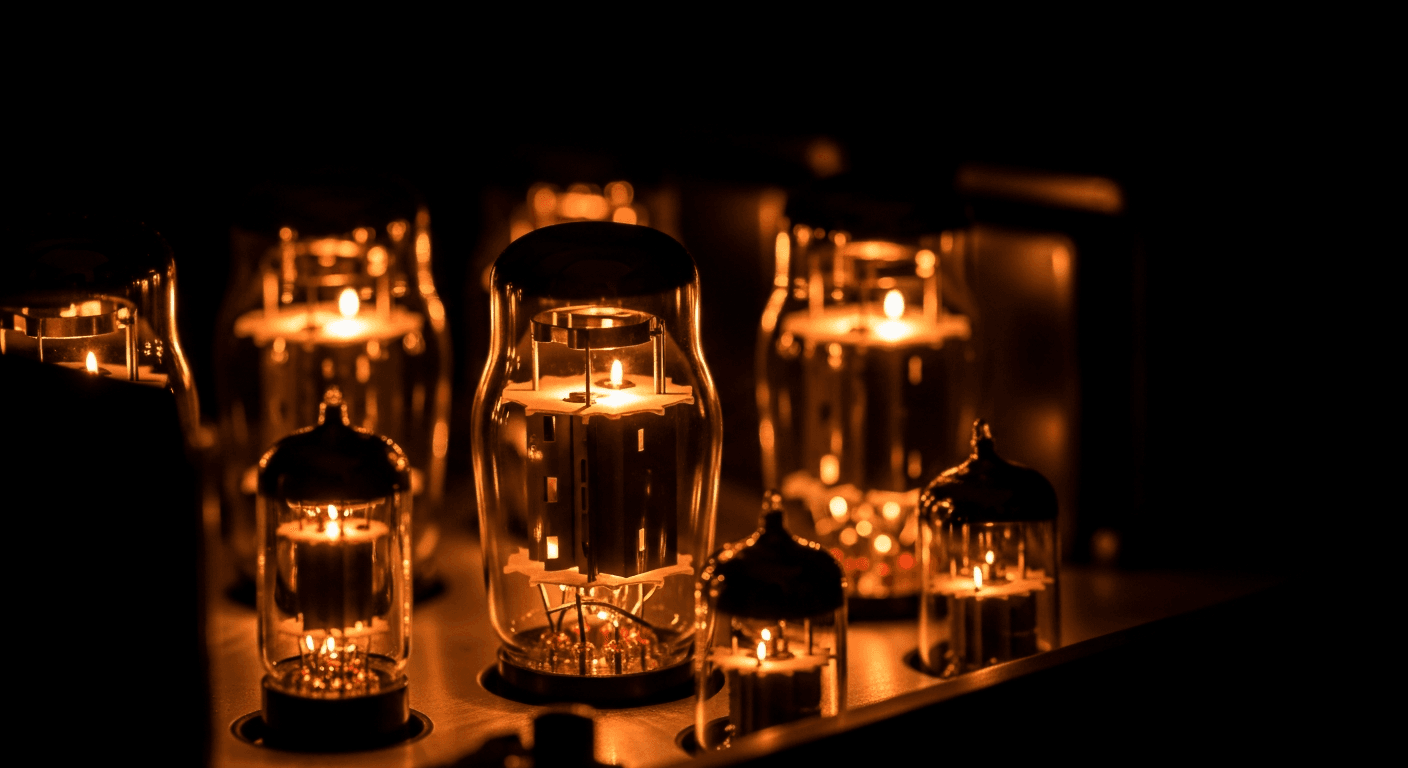

Even-order harmonic distortion. Tubes and tape add 2nd, 4th, 6th harmonics�octaves and fifths of the fundamental. These are musically pleasing intervals. Your brain likes them even when you don't consciously hear them.

Gentle high-frequency rolloff. Analog circuits don't maintain perfect treble response. Transformers, capacitors, and tape all attenuate highs in slightly different ways. Digital is flat to 20kHz. Analog usually isn't.

Soft compression behavior. Tubes and tape soft-clip. When you push them, they don't suddenly distort�they gradually saturate. This sounds "smooth" compared to digital clipping, which is harsh and immediate.

Noise and imperfection. Analog has hiss, hum, crosstalk, channel imbalance. In small amounts, these create a sense of "life" that perfect digital silence doesn't have.

That's it. That's what warmth is. Everything else is marketing.

Why digital sounds "cold"

Digital audio is accurate. Too accurate, some would say.

Every sample is exactly what was recorded. No coloration, no added harmonics, no gentle compression when things get loud. For most purposes, accuracy is great. For music? Sometimes you want the opposite.

The problem is that we spent decades listening to music through analog systems. Records, tape, tube amps, transformers everywhere. Our idea of "good sound" was shaped by those colorations.

Digital gives us the uncolored truth, and sometimes the truth is harsh.

What I learned from modeling analog gear

When I built the Ember EQ, I didn't just copy the frequency response. That's easy. What's hard is getting the behavior right.

Real analog gear responds differently at different levels. Push it and it changes. The EQ curves shift, the harmonics increase, the transients round off. It's dynamic in ways that a simple EQ curve isn't.

I spent weeks just on how the saturation changes with input level. Not "add some harmonics"�but which harmonics, how much, and how that changes based on frequency and amplitude.

Getting that right is what makes something feel analog rather than just having an analog-looking GUI.

How to add warmth (for real)

Here's what actually works:

Saturation, but less than you think. Most people crank saturation until it's obvious. That's not warmth�that's distortion. Real analog warmth is barely perceptible. You feel it more than hear it. Start at like 5-10% and back off from there.

High-frequency rolloff. Try a gentle low-pass filter or high shelf cut around 12-15kHz. Just 1-2dB. This is what tape and transformers do naturally. Your mix will feel less "digital" immediately.

Work the transients. Digital preserves every transient perfectly. Analog doesn't. A gentle compressor or soft clipper on drums can round off those laser-sharp attacks. Doesn't have to be much�just enough to take the edge off.

Subtle modulation. Analog isn't static. Tape drifts, tubes have microphonics, transformers introduce tiny phase shifts. Very slow, very subtle chorusing or pitch drift can make static digital sounds feel more alive.

What doesn't work

Stacking "analog" plugins. I've seen signal chains with tape emulation into console emulation into tube emulation into another tape emulation. That's not warmth, that's mud. Each of these adds harmonics, and harmonics stack up. By the end, you've got more distortion than signal.

"Vintage" presets. Most of these just add noise and roll off highs. That's... not really the same thing. Noise doesn't equal character.

Believing the marketing. Just because a plugin has a wood-panel GUI and the word "analog" in the name doesn't mean it actually models analog behavior. Some do. Many don't.

The uncomfortable truth

Most mixes don't need more warmth. They need better arrangement, better recording, better mixing decisions.

"It sounds cold" is often code for "something's wrong but I don't know what."

Warmth is the finishing touch, not the foundation. If your mix sounds bad, saturation won't fix it. It'll just make bad sound warmer.

Focus on the fundamentals first. Get the arrangement right, get the balances right, get the EQ right. Then, if it still sounds too clinical, add some gentle saturation or high-end rolloff.

Or don't. Some music should sound clean and digital. There's nothing wrong with that either.

"Analog warmth" isn't inherently better. It's just different.

Use your ears. Trust your taste. The goal is music that moves people—not music that fits someone else's definition of what good sounds like.

Ember EQ was built to capture real analog behavior—not just the frequency response, but how the saturation and harmonics change with input level. It's the closest I've gotten to that analog feel in software.

Related Articles

Analog Modeling: How Plugins Get That Sound

What actually happens inside analog-modeled plugins. The DSP behind harmonic distortion, transformers, and tube warmth.

How to Use Reference Tracks: The Pro Mixing Secret

Reference tracks are how professionals avoid mix blindness. Learn to use them effectively without losing your own sound.

Delay Settings for Vocals: From Subtle to Dramatic

How to use delay on vocals without creating a muddy mess. Practical settings for slap, tempo-sync, and throw delays.